For nearly a decade, I worked as an architect in the world of high-rise residential development — designing buildings that, sooner or later, would be inhabited by real families, with real needs. Blueprints, regulations, budgets, permits. Everything had to be meticulously controlled and justified. And although there was always room for creativity, it inevitably had to stay within very defined margins.

However, alongside that “formal” career, I had been developing 3D modeling skills for over twelve years, using tools like Archicad, SketchUp, Rhino, and Grasshopper. What started as a way to better represent my architectural ideas gradually became a language of its own. A personal space for experimentation — which, without me realizing, began to carry more weight than the actual square meters being built.

At some point, I started wondering if my background and experience as an architect could find a place in other worlds. Not metaphorically — literally other worlds: virtual ones. That’s when I began to explore architectural and environmental design within the realm of video game development and digital filmmaking.

Architecture Without Physical Constraints

Designing for video games is not the same as designing for real life — and that difference, far from being a limitation, is exactly what makes it so thrilling. In the real world, things like climate, material availability, budget, and land conditions restrict what we can imagine and build. In the virtual world, architecture becomes a pure form of visual and narrative expression. It doesn’t need to withstand earthquakes or provide solar protection. It needs to evoke, to suggest, to set the mood, to tell a story.

This is where I discovered that the role of the architect doesn’t disappear — it transforms. We’re still designing spaces, still organizing volumes, playing with light, scale, and texture. But now we do it with a freedom rarely allowed in real-world projects.

Architecture as Narrative Backdrop

In games and film, architecture isn’t always the main character — but it’s always a supporting one. A ruined castle speaks of a past, a damp alleyway creates tension, a futuristic apartment reflects a character’s psychological state. In other words, architecture tells a story even when no one’s speaking.

Designing for these media means understanding that walls aren’t just walls, that a square isn’t just a square, and that every choice — from textures to proportions to emptiness — either adds to or takes away from the world being built.

From Real Towers to Virtual Worlds

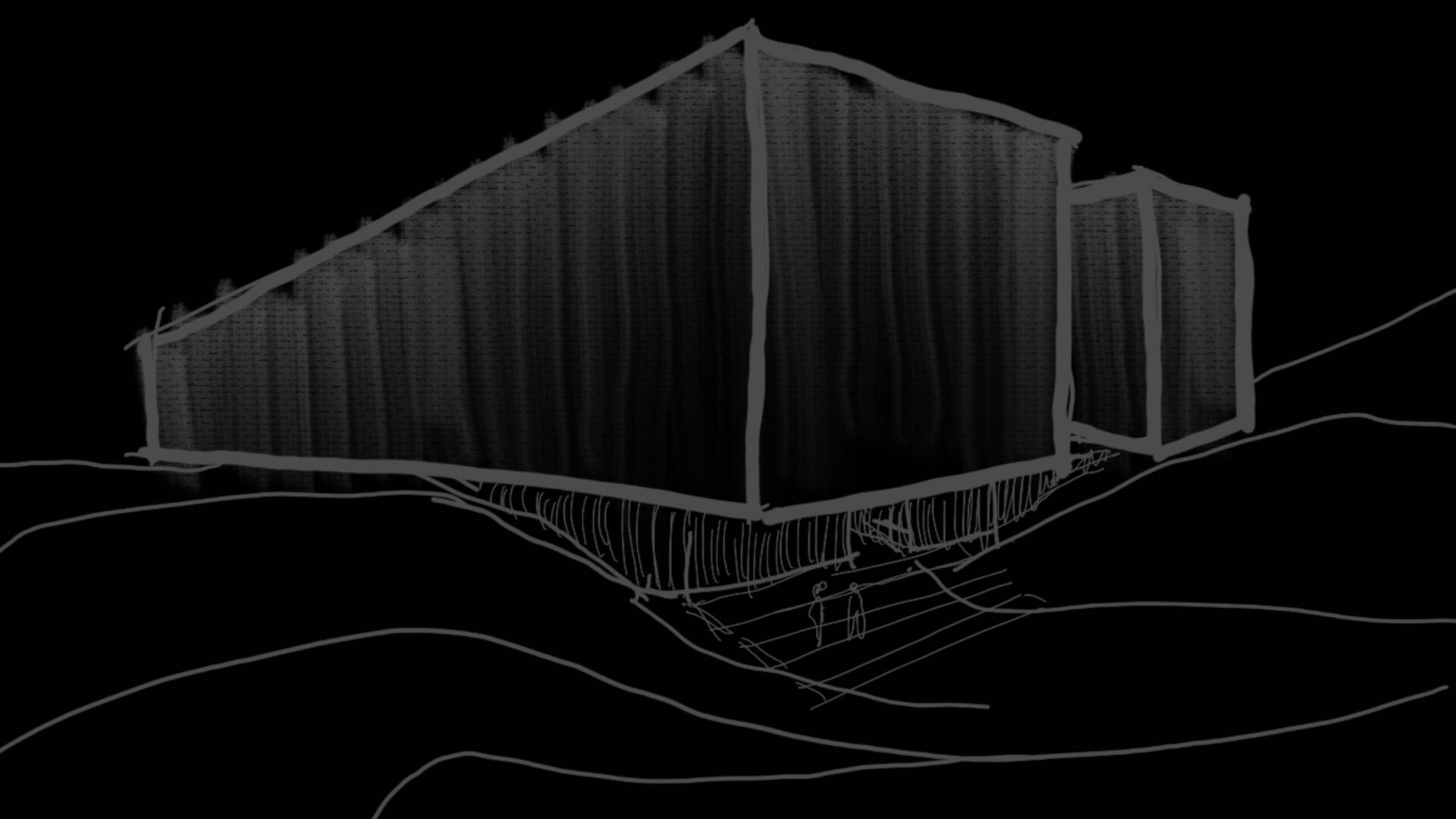

One of the first exercises I did was to take some of my past real estate projects and reimagine them as video game environments. Some worked surprisingly well; others didn’t. The difference wasn’t in the technical design — it was in the narrative: the “why” behind the space, the “for whom,” and above all, the feeling of being there.

That’s when I started designing from a different mindset. Creating spaces not just to fulfill an architectural program, but to express a mood, an aesthetic, or a narrative intention. Some projects began with a visual idea, others with a world concept or even a character. Little by little, I learned to let go of structural constraints and embrace the expressive potential of space.

Beyond Scale: Architecture and Environment

My current work is divided into two main areas. On one hand, I design and model architecture, objects, and detailed furniture — whether realistic or imaginary — with the precision I learned from traditional architecture. On the other hand, I create large-scale urban environments: towns, cities, entire landscapes, where architecture becomes part of a broader system. The level of detail depends on the project — smaller elements are highly detailed, while larger environments are designed with optimized complexity.

Both approaches share the same core intention: to build worlds. Places that don’t exist, but feel just as real as any street we’ve walked. Places that inspire, support a story, and give meaning to a scene.

An Invitation to Rethink Design

My journey from traditional architecture to game development wasn’t something I planned. It was a personal need to reconnect with curiosity, to rediscover the most creative part of my craft. Today, I feel like I’m rediscovering architecture from a different angle — one where technique still matters, but serves visual and emotional storytelling.

My invitation, both to fellow architects and creatives from other fields, is to pay attention to this meeting point. Because maybe, beyond drawings and bricks, what we’re really doing is imagining spaces for others to inhabit — even if just for a moment, even if only in a completely fictional world.